Something's amiss in Lake Tahoe

- Mina Bedogne

- Jun 5, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Dec 17, 2022

A view of Lake Tahoe's northern shore from King Beach State Recreation Area

MINA BEDOGNE/ECO PERSPECTIVES

LAKE TAHOE is hailed internationally for its clear, strikingly blue waters and scenic grandeur. Mixed conifer forests and granitic peaks encircle the lake, attracting the awe of some 15 million naturalists and recreationists each year.

Spanning the California-Nevada border, Lake Tahoe transcends not only state lines but seemingly defies mankind’s tainting influence in an era of mass urbanization.

Growing up in the impervious, concrete heart of Los Angeles, it was hard for me to believe that a place of such undisturbed natural beauty could exist so close to home. Yet, during my first visit to the famed Lake Tahoe basin, its sandy shoreline and mountainous horizon did not disappoint.

From Kings Beach State Recreation Area, situated along Tahoe’s northern shore, the lake appeared as pristine as ever. It would take more than the crowd of picnickers and swimmers to ruin what Mark Twain proclaimed to be “the fairest picture the whole earth affords.”

Indeed, even in the Anthropocene, Lake Tahoe remains an impressive natural wonder in many regards. The 191 square-mile waterbody, surrounded by 72 miles of shoreline, boasts the highest water quality among all large lakes worldwide. It is the second deepest in the United States, after Oregon’s Crater Lake, and holds a staggering 39 trillion gallons of water—enough to flood the entire state of California with over a foot of water.

Yet, as with any natural resource, we humans have certainly left our trace at Lake Tahoe, giving credence to my initial skepticism. Peering into its record-breaking depths reveals a story altogether different from that of a recreational wonderland: a decades-long narrative of exploitation, pollution, and degradation that has slowly corrupted Lake Tahoe’s world-renowned waters and continues to threaten its ecological well-being.

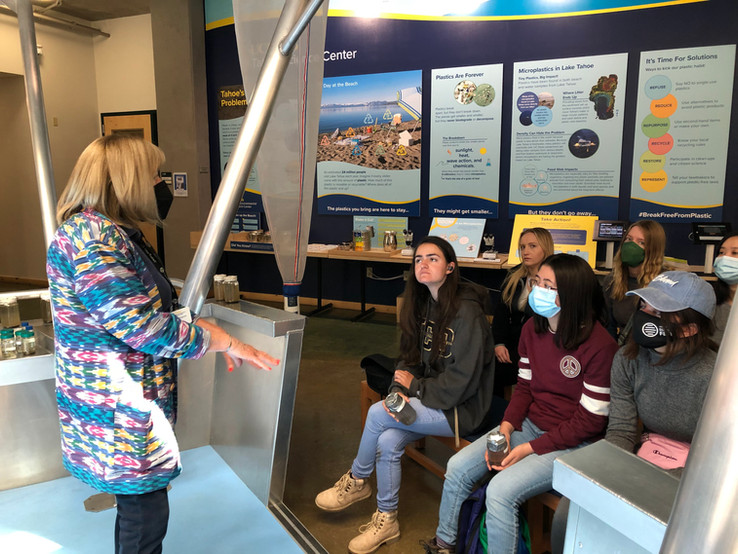

Click the slider for a peek into TERC's Tahoe Science Center

MINA BEDOGNE/ECO PERSPECTIVES

THE ORIGIN of Tahoe’s legendary water quality dates back 2 million years, when faulting, volcanic activity, and glacial collisions sculpted the lake’s modern form. To catch up on this extensive history and uncover the true condition of the lake, I ventured to the Tahoe Science Center in Incline Village, Nevada, an educational hub for new findings from the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center.

Fine sediments (tiny inorganic particles smaller than the width of a human hair), nutrients (namely, nitrogen and phosphorus), and algae comprise the primary factors affecting a waterbody’s health. Historically, these three inputs have been low in Lake Tahoe compared to other lakes. According to Mary Bronson, a science center docent, a few geologic and ecological eccentricities are responsible for this phenomenon.

“The watershed is really small compared to the size of the lake,” Bronson explained, referring to the area of land that drains directly into Lake Tahoe.

This small ratio of drainage area to lake area means that when it rains, a good portion of precipitation falls straight into Lake Tahoe, minimizing the amount of runoff—precipitation that flows across sediment- and nutrient-laden surfaces—entering the waterbody. Simultaneously, surrounding meadows and wetlands act as a natural filtration system, removing pollutants from incoming water.

Additionally, much of the lake is composed of granite, which Bronson calls a “clean rock” because it fractures relatively smoothly rather than breaking into many fine particles. As such, natural processes introduce little sediment into the water.

This lack of sediment and nutrients also helps explain Lake Tahoe’s famed hue. As the clear water reflects the sky, it also absorbs other wavelengths of light without interruption from floating or submerged particles, resulting in a brilliant blue.

Average Secchi measurements from 1968 to 2020

TAHOE ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH CENTER

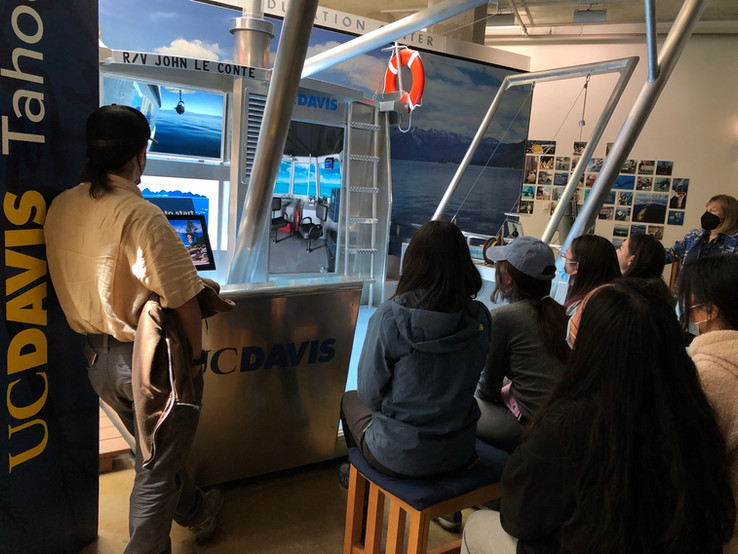

SINCE 1968, the Tahoe Environmental Research Center, or TERC, has monitored water quality in Lake Tahoe to safeguard the immediate environment and apply lessons in limnology—the study of inland aquatic systems—to waterbodies worldwide. During this time, a critical indicator of the lake’s health has been water clarity, which researchers assess using a 10-inch white plate called a Secchi disk attached to a measuring tape.

Every ten days, TERC researchers set out on the UC Davis Research Vessel John Le Conte and lower the disk into the water, recording the depth at which they can no longer see it. The less suspended matter present, the farther down the disk is visible. Researchers can then extrapolate water quality from Secchi readings.

When TERC began its monitoring programs, Lake Tahoe’s clarity averaged about 100 feet. Over the past 60 years, Secchi readings have steadily dropped to an annual average of 62.9 feet through 2020—1/3 of its historical transparency or the equivalent of a standard three-story building.

The primary culprit? Urbanization.

The 1960 Winter Olympics took place at the once-struggling Squaw Valley Resort, now known as Palisades Tahoe, bolstering intense development and infrastructure construction in communites all around the lake.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

LOGGING AND MINING operations in the mid-19th century mark the start of humanity’s destructive influence in the Lake Tahoe basin. At the same time that Mark Twain gushed over the lake’s unparalleled beauty, profit-hungry settlers blasted through geologic wonders, tore down old-growth forests, and displaced the Washoe People, who had sustainably hunted and fished in the area for thousands of years.

Fast-forward 100 years: cement and bulldozers replace axes and minecarts, propelling urban development and increasing the human footprint in Tahoe exponentially.

Much of the development that engulfs Lake Tahoe today emerged from this rapid urban growth in the 1950s and 60s. In the wake of American post-war prosperity, Tahoe’s snowy slopes and crystal waters soon became a playground for the rich. New homes, resorts, and infrastructure transformed the landscape, replacing wetlands with impenetrable concrete and introducing a variety of water pollutants.

“The 1960 Olympics put Tahoe on the map,” Bronson added as she retold the darker side of the lake’s history. “And Highway I-80 made it faster to get from the Bay Area,” solidifying Lake Tahoe’s status as both a domestic and an international tourist destination.

During this time, environmental degradation ran rampant in and around the lake. Urban development replaced upwards of 75% of marsh and 50% of meadows, severely restricting the land’s natural filtration capacity. Furthermore, precipitation that once infiltrated into soils or flowed through wetlands now rushed across impervious roads and parking lots, picking up large concentrations of sediment, nutrients, and chemicals before finally reaching the lake.

A visit by former President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore in July 1997 prompted renewed efforts to improve Lake Tahoe's water quality.

DIANA WALKER/GETTY IMAGES

EFFORTS TO PROTECT Lake Tahoe took root in 1957 when concerned locals established the League to Save Lake Tahoe, the lake’s first and largest environmental nonprofit. The group spearheaded efforts to stifle unsustainable development and generated much-needed momentum for large-scale actions to safeguard water quality.

Amid continuing concern over ecological conditions in the Lake Tahoe basin and with the League’s urging, Congress approved the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA) in 1969—a compact between California and Nevada to streamline cooperative development oversight and the nation’s first bi-state environmental agency.

“Federal funding was allocated for projects to restore the clarity of the lake,” including a regional action plan to achieve newly established environmental standards. “And TRPA monitors what’s going on,” Bronson summarized.

In 1997, TERC researchers recorded an alarmingly low average Secchi reading of 64 feet, triggering an unprecedented presidential visit to Tahoe. In response, leaders at all levels of government collaborated with NGOs, private entities, and the Washoe tribe to establish the Environmental Improvement Program, accelerating the attainment of regional goals.

With the contributions of TRPA, TERC, and the Environmental Improvement Program, Lake Tahoe’s water quality began to stabilize in the early 2000s. Then, in 2011, the Federal EPA approved the Lake Tahoe Maximum Daily Load (TMDL), which it considers “the centerpiece of efforts to reverse the decline in the lake’s deep-water clarity and restore it to historic levels.” This pivotal plan identifies fine sediments, nitrogen, and phosphorus as primary pollutants and sets robust targets to reduce their input.

A sample of some of the plastic waste recovered by the NGO Clean Up the Lake

CLEAN UP THE LAKE

DESPITE THESE ENDEAVORS, Lake Tahoe still suffers from the legacy of its growing pains. Today, urban areas account for only 10% of the land around the lake, yet they produce 70% of the fine sediments that pollute its waters.

“It’s not a one and done,” Bronson confessed. “Time is changing, and other stuff is happening. All these projects are not just continuing to improve this situation.”

According to TERC’s most recent annual State of the Lake Report, nutrient loading remains a principal concern in Lake Tahoe, fueling algal growth in a process known as eutrophication. These algae ultimately diminish the lake’s renowned clarity, degrade the recreational value of the near-shore, and harm deep-water organisms by depleting dissolved oxygen through the decomposition process.

In its report, TERC also provided data on several new, sustained, and interconnected threats to Lake Tahoe’s environmental health, including wildfires, which add smoke and ash constituents to the water, and climate change.

As the Western U.S. experiences increasingly warm temperatures, Tahoe is losing its picturesque snowy peaks, and more precipitation is falling as rain rather than snow. These trends translate to higher stream flows and lake levels, resulting in flooding and infrastructure damage. Simultaneously, the lake’s waters are warming, with adverse implications for aquatic food webs.

During the winter, oxygen-rich surface waters cool and sink downward, causing vertical mixing. But “If the temperature is warmer, mixing doesn’t bring oxygen all the way to the bottom,” Bronson explained, compromising aquatic life throughout the water column.

Lake Tahoe’s dazzling waters also conceal its major plastic pollution problem, which is only now gaining the attention it deserves thanks to work by TERC and environmental nonprofits.

This past May, a group of volunteer divers completed a comprehensive cleanup of the lake’s 72-mile shoreline, collecting nearly 2,000 pounds of plastic waste. While saddening, this amount of plastic is nothing new. As displayed prominently in a research center exhibit, divers collect a whopping 4,700 pounds of trash from the lake's depths each year while volunteers pick up upwards of 1,500 pounds from the shore on the 5th of July alone, much of it plastic.

Especially concerning is the breakdown of plastic in the lake when subjected to sunlight, heat, and wave action. The resulting microplastics—pieces smaller than 5 millimeters—never biodegrade or decompose, entering aquatic food chains and leaching chemicals into soil and drinking water. These smaller plastics are a current research focus of TERC and the Desert Research Institute based in Reno, Nevada, as Tahoe scientists know little about their long-term impact on the lake.

Click the slider for more images of the near-shore

MINA BEDOGNE/ECO PERSPECTIVES

GIVEN THESE ANTHROPGENIC THREATS to Lake Tahoe, it’s easy to see why Bronson considers TERC’s mission to restore and maintain the waterbody’s health “no easy task.” Yet, despite a long development history, continued human influence, and lack of national park status, the lake persists with superb water quality.

On the drive back to my apartment in Davis, I had a final opportunity to witness the lake's dichotomy. Winding along the heavily trafficked highway surrounding the lake, passing casinos, Pilates studios, and the occasional Starbucks drive-through, I truly came to appreciate Lake Tahoe’s resilience. In the distance, its crystal waters gently lapsed across the shore, seemingly in defiance of all nearby development.

And as long as actors from all segments of society continue to collaborate toward environmental goals, I am confident that Lake Tahoe will continue to resist its legacy of degradation.

Academic Citations

UC Davis Tahoe Enviornmental Research Center. (2021, August). Tahoe: State of the Lake Report 2021. https://tahoe.ucdavis.edu/stateofthelake

Comentários